It’s been nearly 2 1/2 months since work at Big Bald Banding Station concluded for Bottfly and I, and I’m ashamed to report that we’ve done little adventuring or birding since. Also, we have neglected (til now) to make the necessary updates and promised posts to Anywhere, Earth…

You might say not one but two fogs have descended upon us; a figurative fog of frivolous distractions and endless job searches, and a literal fog of well…rain and fog. I am happy to report we have come to the end of the figurative fog (though I’m still searching desperately for a job). Unfortunately for the birding, it’s the literally rotten weather that continues. In a way, it’s a continuation of the kind of weather that plagued Big Bald for much of October.

Looking at Little Bald from Big Bald one on of those cold, dreary, gusty October days.

SUNDAY – As soon as I read the post aloud to Bottfly we awoke from a fog and made ready to leave. A loon at Lake Julian thought to be an immature Red-throated two days before turned out to be of the Pacific variety. What better way to mark our glorious return to birding after a 2-month absence than picking up a Pacific Loon? And only 20 minutes away?

We arrived and were immediately disappointed. A group of recreators were already on scene, driving a loud, obnoxious RC boat in the general vicinity the loon had been seen in the day before. Then the rain arrived; a sprinkle at first, growing to a light, steady shower that drove the recreators away. A placidity was restored. The lenses of our optics were grayed with moisture as we scanned the ripples of the lake, hoping to catch the loon as it surfaced.

We searched from various vantage points with nothing to show for it but a few blurry glimpses of distant Pied-billed Grebes, so we decided to try from the area where the remote control boat had been driven from. Without getting our hopes up, we scanned the lake to the opposite bank and spotted a larger diving bird, accompanied by a smaller one, surface then submerge. The smaller Pacific Loon was seen the day before in the company of a larger and bulkier Common Loon – our excitement began to cautiously rise. The wet lenses, distance, lighting and our rustiness were preventing us from getting a positive ID on either bird. The larger bird was definitely a loon; the smaller one had barely stayed up for a second before it vanished completely, but I was beginning to think it was another grebe.

Another birder had showed up; a middle-aged woman whose name I forget had started to scan the same area and was having little success getting on the birds, which both seemed for the moment to have disappeared. Another birder arrived, scope in arms: a sophomore from Western Carolina named Mike. After a few minutes of attempting to relocate the birds in question Mike suggested we try scanning from the dam access road, which could provide a more favorable viewpoint. Minutes later, our small convoy arrived and we immediately spotted a Common Loon. As Mike exited his truck he informed us of a post he had just received – the birder that originally found the loon had searched that same morning for the two loons, but found instead a Common Loon entirely different from the one seen 24 hours previous. It appeared that both loons had departed and that we were looking at a new arrival.

We searched a while longer then admitted defeat. We had scanned much of the lake and saw only the one Common Loon and many Pied-billed Grebes. It didn’t look like the day would be ours after all. We said goodbye to our fellow birders, happy to have met and to have shared the search with them, happy to have gone birding again – even if we didn’t find the birds we were looking for.

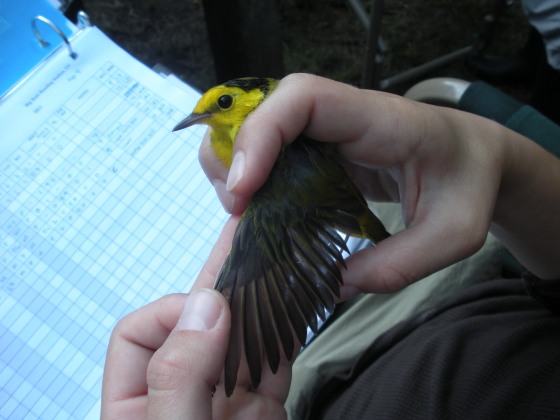

That’s all for now. Sometime over the next few days we will be traveling to Hiwassee Refuge to attempt the Crane Trifecta…A Hooded Crane, which breeds in Siberia, has somehow shown up in Eastern Tennessee and has been seen in the company of thousands of Sandhill Cranes and even a few Whooping Cranes for about a month now. Also in the works is a trip to the OBX possibly later this month, maybe the beginning of February. Keep checking back, as we’ll continue with (at least) weekly updates on our past trips or posts about Big Bald. For now, I’ll leave you with a couple pics of some sweet Big Bald birdage.

Blue Jay - what a handful! Blue Jays, though notorious for being loud and bullish, are quite docile in the hand. Amazing bird.

Hatch-year scarlet tanagers. Notice the difference in coloration of both wings; the male (left) shows a darker wing even at this early age than the female (right). These birds were caught side by side in the same net. Could they be brother and sister from the same nest?

Yepoh searching for contrast in the wing of a Hairy Woodpecker. The station had a nice diversity of woodpeckers this season, including Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Downy Woodpecker, and Pileated Woodpecker.

Bottfly with a Blue-headed Vireo. I can't recall the age or sex of this individual, though most Blue-headed Vireos we catch tend to be younger birds. One of my favorite birds of the Southern Apps! Such sweet songs!

Male Rose-breasted Grosbeak, hatch-year if I'm not mistaken. Pulling this species out of the nets can be a painful experience if you aren't careful. They can bite! Additional caution was needed with this individual - the new (pin) feathers coming in on the wing (to the right of the large white patch) are full of blood vessels and if caught in the net they can break, resulting in injury to the bird.

Yepoh examining a Wood Thrush. Another one of my favorite birds. Thrushes are quite arguably the best songsters.